Erika

Posts by Erika

The Beginning, the Middle and the End of 29 1/2

In 2000, my friend, the very kind and talented engineer Richard Marr, suggested that I come up for a few days to his house in Boston where he had his home recording studio. I could crash on his couch and record five or so songs, and he’d get to know Pro Tools, Version God-Knows-What, in the process. Lately, I’d been drifting; the band in which I’d invested all my creative energy fell apart as too many band members wanted to be the boss, and no one of us were willing to cede to any other of us. It was the typical ego stuff that plagued many quasi-professional rock outfits, and after having put what money I had into the band’s recording, I was broke.

In 2000, my friend, the very kind and talented engineer Richard Marr, suggested that I come up for a few days to his house in Boston where he had his home recording studio. I could crash on his couch and record five or so songs, and he’d get to know Pro Tools, Version God-Knows-What, in the process. Lately, I’d been drifting; the band in which I’d invested all my creative energy fell apart as too many band members wanted to be the boss, and no one of us were willing to cede to any other of us. It was the typical ego stuff that plagued many quasi-professional rock outfits, and after having put what money I had into the band’s recording, I was broke.

Richard’s gift succeeded in its mission. He produced a beautiful sounding record and the project lifted me up, steeping me in the creative process after a disappointment. We went deep and added six more tunes to the original promised five. We had an album! It documented a handful of my solo-songs, all written over a span of five years.

I loved – and still love – this record. It serves, like all records of events, as a diary entry, and this one, a document of my youth. This means it conjures partially my embarrassment (only some lyrics), and mostly my admiration. There’s beauty, fun, and of course, some super-powered female anger, which I can get behind, but no longer reproduce. That’s a vitality issue.

When 29 1/2 came out, I celebrated its release at a local club, “Pete’s Candy Store” in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. My friend Todd Satterfield, who was the guitarist from the previous band, joined me on stage. Todd had come up to record with me that week in Boston, because, I guess he had nothing better to do, post-band-breakup, either. His voice and playing everywhere on that recording certainly makes the beauty of the record.

Soon afterward, having played a bunch of tri-state area shows, I planned a solo acoustic west coast tour. When I mentioned this to my mother, it appeared to concern her. “But where will you stay?” When I reported that there was a network of friends of friends from San Diego to Seattle, who’d said I could sleep on their couches, she either saw an opportunity for herself, or wanted to possibly protect me from this catch-as-catch-can, sleep-wherever-the-heck solo woman journey, or both.

“Maybe I’ll go with you”, she responded. “We can stay with my high school friend in southern California, and you have Jen in Santa Cruz, Chris in San Francisco, then we’ve got Christa in Portland….” As we proceeded to compile our list, we realized this was a viable plan, and within a few months the tour was booked.

I flew out first, meeting my mother after the first couple of shows. The very first one had me opening up for the mystical Tom Brousseau. It was the first time I’d ever heard him perform; he played with a friend of his somewhere in southern Cali, and I was appropriately blown away. Here I was, absolutely playing out of my league, but I didn’t care. I simply allowed myself to get lost in these powerful performances. I gave him a CD.

Following that kick-off, the mother-daughter road trip began at LAX, where I picked her up in the rental car and immediately told her all about this musician from North Dakota with a voice like Jimmy Scott. My mom, who was a singular mix of control freak and more of a rebel than me or you or anyone you know, pretended to listen to me while immediately securing her place behind the wheel. I can only assume it was her anxiety of being in the passenger seat on winding 101 that propelled her lead. Since this was pre-GPS and we had only AAA and the Texaco Road Maps to illustrate the route that we’d meticulously highlighted prior to our trip, I was responsible for navigating.

In the tight streets of a small city, she asked, “Should I do a U-turn here?” “I wouldn’t,” I said, inferring that we should probably make a right and another until we were back on track, before she whipped the car around in the middle of the boulevard, running up over the curb. “Well, I know YOU wouldn’t…” she said impatiently.

On one of our long drives to the next stop, she suddenly pulled over to the side of the road along the California coast. Ah, I thought, she finally needs a break. But she swiftly popped the trunk and stepped out, rounding to the rear of the car, from where she pulled out two bottles — one of vodka and the other of orange juice — and magically produced two plastic cups from her purse. She mixed the drink clumsily and handed the cup to me, before pouring another for her. We got back in the front seat and watched the sun descend brilliantly into the Pacific, before moving on to a seaside restaurant and laughing until our sides practically split. I don’t remember what we laughed at particularly, and it doesn’t matter; it was all just a classic case of the giggles.

Diligently each night, my mother sat at the merch table, selling one or two CDs to whomever came out for these sparsely attended shows, and running herself back and forth to the bar to get the appropriate change for buyers. I had t-shirts made for the “Where Can I Get A Good Bagel Around Here” Tour, my west coast joke that really wasn’t funny, listing the stops in the cities on the tour, with the cliche ‘Sold Out’ stamp across the back. I no longer have any of those, thankfully, so I either sold them out, or threw them out.

For seventeen years after that, I stored the excess boxes of 29 1/2 in my mother’s basement. On visits home, she’d occasionally ask when I’d be taking them, but of course, my one-bedroom apartment didn’t allow me the luxury of storing my own stuff. But I knew in the now streaming music era, there was no way I was ever going to get rid of those CDs.

When my mother sold her house to move into an apartment three years ago, I traveled to South Jersey for a long weekend to sort through my things. On the way down, I brainstormed ideas about what to do with the CDs, at this point, mostly not wanting to throw that amount of plastic into a landfill. Other family members descended to help with the moving-out effort, and we all spent the weekend clearing and cleaning. On Monday morning, as I heard the garbage crew approaching, I watched my mother dash outside in her purposeful walk toward the truck.

“I struck a deal with the guys,” she said, wiping her feet and closing the front door behind her. “They said you can put all the CDs out and they’ll come back later when they’re picking up recycling.” I wondered, really, what was the actual “deal” my mom struck, but I didn’t ask, because almost twenty years later, this felt like a triumphant ending. I was too afraid to press her for details on whether or not these would actually be recycled, because I couldn’t risk the truth. Instead, I hauled box after box of CDs to the curb, and plucked only two wrapped copies out of an open box, deciding those would be all I’d ever need.

You can hear it now too, if you like: I just now gave it its streaming wings at https://littlesilver.bandcamp.com.

I am forever grateful to all the people who helped out with this endeavor FOR NO MONEY AT ALL, which today appalls me, but that’s what we did then — played, sang, whatevered — on each other’s records. And then there’s my mother; a good mom supports your dream when it’s happening, and helps you close it up when it’s run its course. And do I hope that somewhere in a South Jersey dump, a sanitation worker is listening to “Long Day in a Short Skirt”? I do.

Alive at the Party (Written in Summer of 2020)

In early July I drove six hours from my home in Connecticut to Maine, to pick up my mother from her assisted living facility and bring her to live with me, my husband, our two daughters, two kittens and four chickens. My stepfather had passed away at the end of June of pancreatic cancer, and none of us had been allowed to visit due to Covid-19 quarantine restrictions. We followed his decline by email and phone for weeks, a gradual fall which was punctuated by the three days of silence between his last phone call and his last breath. He had been the lucky one; my mom, duty-bound, had survived long enough with her own metastatic cancer to shepherd him to wherever he needed to go.

In early July I drove six hours from my home in Connecticut to Maine, to pick up my mother from her assisted living facility and bring her to live with me, my husband, our two daughters, two kittens and four chickens. My stepfather had passed away at the end of June of pancreatic cancer, and none of us had been allowed to visit due to Covid-19 quarantine restrictions. We followed his decline by email and phone for weeks, a gradual fall which was punctuated by the three days of silence between his last phone call and his last breath. He had been the lucky one; my mom, duty-bound, had survived long enough with her own metastatic cancer to shepherd him to wherever he needed to go.

While my mother appeared to accept that she would die without any family near, I could not, so I broached the idea with her hospice nurse, John, of moving her in with us. I expected him to let me down easy; she was currently in the hands of experienced caregivers, not to mention the extra exposure involved in bringing her to a house with two children during a highly contagious pandemic.

“I think it’s a great idea!” he said. “Wouldn’t she rather be with your family than live the two months she has left up here alone?”

“So you think she’s only got a couple of months,” I whispered, turning away from my ever-present children. “And you think we can handle this…”

“I think your mom and dad were living for each other, is all. And yes, you can do this.” John said.

The fact is, I wanted to do it, and more importantly, I wanted to be able to do it. So when we offered this new living arrangement to my mom, her vulnerable and surprised response not only flooded me with guilt, but struck me as out of character for the sharp-as-a-tack, funny and practical person I’ve known her to be.

“I didn’t think you’d want me, and, you know, I don’t want to be a burden.”

It’s a cliche we’ve all heard, and yet a sincere one to which I can wholeheartedly relate. I am old enough, at 48, to recognize the gradual decline in my physical abilities. Though these changes are currently minor and un-limiting, they give me an unobstructed view of the steep slope; I don’t jump with abandon on a trampoline anymore, but I’m proud to say I spend a normal day in dry underwear. The time will come, though, when I will no longer brag about basic maintenance, and I do not want to burden my children’s blossoming lives with my faltering health.

Without any further arguments, my mom agreed. Once in our home, it didn’t take long for her to settle in.

“Put my mirror there. No, not there, to the right. Yeah, better.”

“Make a copy of these pages, not these,” she says, thrusting a lengthy legal document into my hands.

Noticing me strapping on skates one glorious August day, she sees not a much-needed chance for me to get exercise, but rather an opportunity for herself. “Oh!” Her eyes brightened. “Do you wanna rollerblade to the liquor store to get me a bottle of gin?”

One day last week, my younger daughter asked my mom, her Nanu, if she likes crosswords. As my husband, Steve, and I struggled to understand whether she’d said ‘crosswords’ or ‘curse words’, my mom decided it wasn’t worth differentiating. “Doesn’t matter,” she said as she eased onto the couch. “I like both — curse words and crosswords.”

Despite the fact that the last several months have felt like one long customer service call to Xfinity, T-Mobile, Cigna, Hospice, TD Bank and a slew of others, we love that she lives with us. My husband and I no longer exist solely as toiling parents who tag-team childcare, food prep and our work-from-home schedules. With my mom around, we too get to be kids again. “You can do no wrong, Steve,” she says, reaching up to pat his shoulder as she passes him in the kitchen in the morning on her way to the coffee pot. “We’re all so lucky,” she declares, “and I’m happy and relaxed for the first time in my life.”

Our kids have another adult in the house (and arguably the most interested, at this point?) to bounce their zany ideas off of while squirming in and out of her hospital bed all day. Our normally camp-centric, busy summer was replaced with day after day of unstructured time — even boredom. I wondered, when life resumes to a more normal schedule, how will my children categorize this time? How lucky they are to be bored, I thought. There are arguments that boredom leads to creativity, and sometimes it does. Mostly it led to more movies with their Nanu.

A week ago, my older daughter and I got into an argument, which ended with her screaming at us all, to get out of her room — a first since my mom had arrived here. Nanu easily obliged; she doesn’t get bent out of shape, but rather, spends her time doing NYT crosswords and watching serial killer shows on Netflix. After my daughter and I made amends, she went into my mom’s room for a bit, and later reported in confidence, “When I apologized to Nanu, she calmly told me, ‘You can yell at me all you want. It doesn’t matter, because I love you so much.’”

One could question — is this helpful? And in these times, I can’t imagine how it isn’t. My mom is living through this pandemic nightmare with us, throwing us an extra emotional rope. The gift of this horrible, confusing moment on earth — environmentally, emotionally, politically — is, we don’t have to miss each other now that Nanu lives with us. Everything that felt like the painful tug of impending loss before she moved here has evaporated. I will miss her terribly when she’s gone, and that will be relatively soon. She is in hospice care, is in and out of clear thinking, and ingests a timed and consistent cocktail of narcotics for pain management. She has undergone so many surgeries she doesn’t even recall all of them, but I know they happened, not only because I remember, but from the scars that line her body. Last weekend she abruptly went from bustling around the house on her own to being immobile in her bed — an overnight plummet. I thought back to two days prior, when I leaned against the door jamb in her room, observing as she slowly and quasi-meticulously made up her bed with new sheets. I had to resist the impulse to help.

“You know,” I started, “I was wondering if you’d rally into a new life once you were here with all of us, or if you just finally feel relaxed enough in this environment to die peacefully.”

“Yeah, I don’t know,” she said, backing herself onto the bed and reclining. “I think it’s a little of both.”

Going Pro – 10 Years In!

Ten years ago today, Little Silver tied the knot. “You’re going pro” people liked to say to Steve and me. This referred to our marriage, not necessarily to an uptick in the professionalism of the band. But it is the day that, on a ceremonial level, brought our energy-toward-all-things-in-life even closer together.

I was a late bloomer with most things, and marriage was no exception. My mom, married at 21 and divorced at 36, always advised, ‘Wait as long as you can to get married, because you’ll change so much in your 20s.” I pushed that, and by 36, I’d lived 14 years independently, earning my money, paying my bills, etc. My expenses were few, my taxes uncomplicated. I wrote and recorded music with friends, planned and executed solo tours, and when homeopathy majorly helped to bail me out of a long-standing illness, I went back to school to study it and opened my own practice in Manhattan. I ran the daily drama gamut – good times, accomplishments, failures, loves, regrets, etc. To be honest, I barely remember much of it at this point, and I wasn’t drunk or high for 14 years, either. It just all fell under the heading of ‘the same kind of feeling.”

When I met Steve I really liked him, and not romantically. Any of you out there who know him know he’s quite the likable person. I welcomed his mix of open heartedness, optimism and his slam dunk of a sense of humor. Many months later, when the moment came that he made it known to me that he was available, I felt every cell in my body relax at once. A full-spectrum ‘Of Course.’ When we started writing and singing together, our voices, both of which had done fine on their own up to that point, blended to form a new texture.

As a feminist, I have a problem with the ‘you complete me’ model of partnership. One reason I never liked Jerry Maguire, actually, is that clincher line lost me at the end. (Side note: it’s a weird experience to be let down by the finish line of a movie to which most everyone related so heartily, but admittedly I’ve endured worse.) But here it was right in front of me; our two voices sounding like one, but with just enough definition that you could tell who was who. I liked that, and that’s what our marriage has been like. There’s a push and pull for sure on any given day, but at the end of that day, you can tell who is who. Plus, writing and singing emotionally complicated songs about partnership with my partner keeps things just weird enough for my tastes.

Ten years in and I’m still amused by, and ever-grateful for you, Steve – my best friend and life-love, complex-taxes and all.

Little Silver #7 – Oscar

“Listen, my children, and you shall hear

The midnight ride of a can of beer.

Down the alley and over the fence

And into my stomach with 15 cents.”

Rather than trying to describe my grandfather, Oscar, I thought I’d let him introduce himself.

—-

Feb. 7, 1976

Dear Connie, et al,

Here we are in the midst of a veritable winter wonderland… I wonder how I’m going to pay the oil bills and Betty wonders why she isn’t in Florida – the reason for which is my fault. Of course she is right as always, but her attitude does little to enlist my sympathy. What little I possess is required for my own sad state. I always save a little sympathy for myself — God knows where else I would obtain any. I tuck away any small surplus I find myself occasionally possessed of beyond that which I immediately require, secreting it in concealed little spots, and when I am alone and not pressed for time I drag them out and line them up and feel and fondle and admire them, the agonizing sobs, the tears, the pain wracked spasms. Self-sympathy is great. If cultivated with diligence and devotion it can replace all other motivations and activities to which one has become accustomed.

Well, we had a jolly old shovel out yesterday and this AM, ridding our deck and driveway of a generous accumulation of snow and ice which had fallen and hardened into the embryo of a monstrous glacier. As I say, yesterday and today we aborted it and now the snow is again tumbling in stifling clouds of fluffy cotton and piling our deck and driveway once more to a back wrenching depth. If I get this letter finished before the mailman comes dashing up in a swirl of snow it will go out today. I can hear him when he is coming these days… the barking and yelping of his mush mush doggies. We don’t tip the mailman any more, we throw a little blubber to his huskies.

The mail came and I didn’t hear it. The dogs were silent, choking no doubt, on a frozen herring. There was a letter from you, mentioning all the books you have read by Morris West. I know I read Salamander and the Tower of Babel. I don’t recall being extremely impressed by either of them. I did watch Roots. Mother didn’t but she has become a hostile, verbose authority on the production. I think that by not viewing the drama nor reading the book she can maintain a detached, objective viewpoint from which to offer a true, unprejudiced assessment of its dramatic value, an assessment with its faultless accuracy undiluted by any knowledge whatever of the subject under judgement.

Sorry we have to tell you about your ancestors. On your mother’s side, they were a rotten, degraded bunch. They weren’t exactly horse thieves, a relatively honorable vocation. They stole horse manure. They could always be found marching in the rear of a parade. Your great, great grandmother was a lovely Celctic druidess who had an affair with a baldheaded ape who had fuzzy red hair growing between his shoulder blades. This has been a family characteristic ever since. We try to catch the kids and shave it off when they are quite young. When they get a little older they scamper about like Hell and is it he devil’s own job to capture them. On your aristocratic father’s side you are the descendant of a long line of blue-blooded nobility. The first one who crashed the pages of history came to England from Normandy with William the Conqueror. He was known as Sir Oscar of Cavendish, and is remembered for his famous quote “Willie I will be behind you all the way.” And William’s equally famous answer, “Sir Ozzie, if I hadn’t known you were behind me I would never have conquered England, and if I had known how far behind you were, I would never have attempted it.” William was a great kidder. The Candages fought in every war the United States ever engaged in, but the only one they ever volunteered for was the Whiskey Rebellion. It was a sobering experience, so he deserted. It was during this fierce conflict that he wrote a song called “Getting Bombed on the Potomac”. This was later revised and the name changed to “The Star Spangled Banner”. They deleted the three hiccups which followed “…the land of the brave.” A Candage was one of the most popular soldiers in the Civil War on both sides. He will long be remembered for his strong penchant for wearing ladies’ underwear.

I enjoyed Esther’s book. The people she mentioned and the archaic activities she described recalled things to my mind I had not remembered for many years. Sights, smells, tastes, etc. Chopping wood with Dad and George was a strong point of recall. The clear air, the smooth snow in the woods until we broke a trail with our boots, the smell of the pine and the spruce trees, the tracks of rabbits, foxes, deer, porcupines and now and then a bob cat, the bite of the axe blade in the trunk of the tree and the scatter of the chips. The hot fire to warm our lunch at noon, the neat piles of cord wood placed to assure easy loading on the horse drawn sleds when the cutting was all finished for the winter. A real nostalgia kick! We didn’t know what an energy crisis was. In the winter the automobile was jacked up on blocks and the battery and the tires removed for purposes of preservation, and the jingle of sleigh bells replaced the raucous blast of the horn. And the only exhaust was contained in the steamy breath of horses or oxen expelled from the velvety nose of the horse or the rubbery nostrils of the ox. The world was just emerging into the mechanical age and we so foolishly labeled it progress. Instead of ecological disaster. And we all wanted to get away to the city where the “action was”.

I will now go to get the Monday morning papers and mail this.

Lots of love. Write when you get the time, but don’t feel compelled.

Dad

——-

This is one of a hundred or so letters Oscar Candage wrote to his daughter, Connie—written in such volume that many were simply dated “Monday” or “Thursday”—after he retired from his 30 year career as the Providence Journal’s photoengraving superintendent. Alex and I were toddlers, soon to move with the family to Little Silver, NJ, where Oscar himself would come to live during the last four years of his life.

Early in 1973, Atkin’s job transferred him to Chicago, so he and a pregnant Connie packed up their things, me among them, and headed to the midwest. I suppose Oscar’s letters began at that point, when the long distance phone charges seemed formidable. Bi-weekly, he planted himself before the Smith-Corona typewriter that sat at his desk, overlooking the Long Island Sound in my grandparents’ small coastal Connecticut house.

A little background: Oscar (born 1909) grew up the son of a veterinarian in Blue Hill, Maine. Young “Doc Candage” accompanied his father in a horse and buggy on his rounds to the farms, and the nickname stuck with the old timers throughout his life. Of course, by the time he died, his memorial service was populated by teenaged kids in Little Silver, none of whom called him Doc.

The original Doc Candage, the veterinarian, died of Bright’s Disease when Oscar was 6 years old, and his mother remarried a strict Baptist, which was one of a few reasons why Oscar snuck out of his house at night to drink moonshine with his Native American friends who worked the Maine fields. And like many men of his generation, Oscar was a WWII Veteran. He was stationed in the south of France until he landed a head injury and a purple heart medal, the former from an incoming bomb that crumbled ruins over the dugout where he and his cronies were playing poker. A direct hit, and everyone covered with bricks. When they dug through the rubble, Oscar was the only one still alive and after a brief hospital stay, he was released to a family in France to recuperate for nearly a year. My Grandma Amy, saddled at home with their one-year-old daughter, wasn’t too happy to see the pictures he brought home of him cuddled up with the daughters of his French host family, but when Oscar finally arrived in New York Harbor, he met then two-year-old Connie for the first time, and the three of them moved from Jackson Heights to Rhode Island to start his job and family life.

Against all this as backdrop, Oscar was an artist. He painted watercolored nature scenes on anything he could find, and he drew cartoons; all of our birthday and holiday cards consisted of slightly perverse depictions of the occasion: my grandmother holding a knife in a stand-off against a turkey, or us rolling down a hill toward a giant Christmas tree, or two frogs at a candlelight dinner in France, unaware that their legs were being observed by the chef from behind a curtain. Oscar was also color blind, so his cards and cartoons depicted, for instance, red or purple candle flames—not orange and yellow—which made his greetings a bit more intriguing to Alex and me.

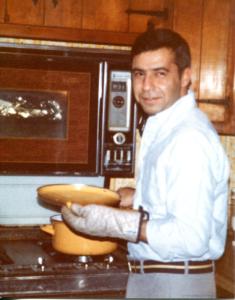

As for the realities and intensities that life inevitably tosses up, Oscar appeared to meet them with a level-headed gentleness, perhaps a touch of alcohol, and always with a sense of humor. He saw the world around him through a slightly absurd lens, occasionally riding his dentures out on his tongue, mid-conversation, for example. And when he drank his daily cocktail(s), he seemed to get a little sillier and more joyful, the sign of a gentle, if not slightly detached heart. Granted, I was his grand-daughter, but I never heard him raise his voice to anyone. And all of us—from my and my brother’s adolescent friends, to my father, to my mother’s friends, to the woman who cleaned the house—adored him. After Oscar bought out Atkin’s half of the house and moved in with us, my father would drive him to his doctor’s appointments and come over to chat for an hour here and there while my mom was at work. My dad really came to life during those visits and, I think, especially loved Oscar not only because Oscar was kind and reliable for an entertaining conversation, but also because he was fatherly—and Atkin’s own father had been decidedly absent throughout his life.

By the time he lived with us, Oscar spent his days reading the New York Times, drawing, writing, singing loudly through his oxygen tubes (he had emphysema from 30 years of smoking, and lugged a carrying case of oxygen throughout the house), and devising entertaining ways to ask my brother, me, and our friends to microwave his TV dinners or mix his drinks. Our house was close to the high school, and friends would often stop over for a few minutes on their way home to have a word or two with Oscar. My friend Jeanene, in particular, loved to wait on him. “Let’s go home and make a banana bread for your grandfather!” One day, in describing a visit to the doctor, he referred to the nurse as a “hot sketch” at which point Jeanene doubled over in near-hysterics and refused to leave the kitchen for the rest of the afternoon. As you may have noted from his letter, he was able to make a day where absolutely nothing happened sound colorful, so you can imagine what he could do with a small encounter.

My brother, who was only then a budding recluse, probably spent the most time with him. While Alex peppered the conversation with one-word prompts, Oscar regaled him with stories of his childhood. This is noteworthy because Alex otherwise, no matter the company, spent almost all of his time hidden away from us. It was from Alex that I learned of Oscar’s midnight escapes to Native American moonshine get-togethers, his war stories, and his and his step-brother George’s shenanigans when they were boys in Maine. Oscar was not one to interfere or try to teach lessons; as a matter of fact, if he had one lesson, it was “take a risk”. And while he tried to toe a line if pressed (“listen to your parents”), his stories often implied, “…but not too much.”

I regret that I was a pretty self involved teenager during the time Oscar lived with us. He had just turned 81 that December, and on an early January afternoon, he uncharacteristically called to me from his bedroom. I cracked the door and he looked to be in pain, seated on the corner of his bed. “I think you’d better call an ambulance,” he said flatly. I didn’t question it, and one pulled into our driveway 10 minutes later, carting him off to Riverview Medical Center where he died 2 weeks later of kidney failure. My mother and her friend Peggy read him T.S. Eliot poems each night as he twitched—and, we thought, smiled—from his comatose state. Alex and I accompanied Connie on each hospital visit during those two weeks. I remember my mother’s conversation at the nurse’s station, asking what she needed to have in place at home for him when the nurse finally told her softly, “He’s not going home.”

Oscar’s memorial service took place in our family room a month later, and we have a kid-filmed VHS tape of it somewhere. Sixteen teenagers and eight adults, my dad included, sat in a circle talking about the character he was, what everyone had learned in their time with him. The event was filled with laughter and wonder before Alex closed by reading a poem of Oscar’s that showed, I guess, how he had felt in darker moments, and why, I suppose, he met the world with a combination of sensitivity, humor and ultimately, irreverence.

“Dreams of nothing surround us

An instant in time is forever

A century less than a second

and eons are endless, but never.

We raise our arms unto heaven

And wave them aloft in the air

And heaven can have no existence

For nobody answers from there.

We’re lost in an ocean of nothing

Adrift on an endless expanse

Our minds discern figures where nothing exists

As we whirl in a meaningless dance.”

Little Silver #6 – The Housekeepers

For five years after Atkin and Connie split up, it was a revolving door at 301 Rumson Road in Little Silver. Connie had taken an executive assistant job in the Big City of Hope and Dreams and hired a host of elderly women to look after Alex and me during the work week.

For five years after Atkin and Connie split up, it was a revolving door at 301 Rumson Road in Little Silver. Connie had taken an executive assistant job in the Big City of Hope and Dreams and hired a host of elderly women to look after Alex and me during the work week.

Number one was Lita, an endearing Filipino lady in her 60s, who wore big glasses and an even bigger bun on top of her head. She used wide, toothy smiles to communicate with us, and since she didn’t speak English and Alex and I spoke no Filipino, this was the most positive non-verbal communication we could all manage. I imagine that she understood us, but I found it awkward, I guess, milling around the house and smiling.

“But don’t you love her baked chicken?” my mother encouraged. I paid special attention after that, finding it just okay — mostly, I wanted it to be great so I could agree with my mom. When Friday finally arrived, Alex and I breathed a sigh of relief and looked forward to Saturday morning when my mom, brother, Lita and I would climb into the car to deliver her back to her husband in Carteret for the weekend. And so on it went, week by week, until it was Atkin’s turn to move back into the house, at which point Lita gave her notice because her husband didn’t want her living in the house of another man.

Our next score was Aunt Jill, the Rock of Gibraltar. I’ve published an entry solely about her so I won’t go into more detail here, but she became a bonafide member of our family for the next three years before she retired, at which point Connie resurrected her ad and up turned Maria.

Maria was Hungarian, again in her mid 60s, and another whose thick accent Alex and I struggled to understand. She too made a mean chicken dish and was overall a fabulous cook and seamstress to boot. For fun, she spent her days hemming and mending our clothes, and one evening when Connie arrived home from work, Maria surprised us all with thick, heavy, yellow curtains for our den, a room that drew in the heat of the afternoon sun, Hades-style. My mother, unable to filter her initial reaction, said softly, “But I don’t like them,” to which Maria responded, “Well, I’m the one who has to sit here, not you,” and up the curtains went. But again, Maria’s tenure came to a close when my father was due to return for his 6 months, because (as we’d heard before) her husband didn’t want her living in the house of another man. Nobody seemed to want to cop to the fact that my father was in his early 40s and these women could all have been his mother, but we were living in the old world, I guess.

This time around, it was on my dad to hire somebody and along came Pauline, an Italian close to 70. She drove a royal blue Lincoln Continental and owned a trailer behind the mall. Pauline wore housecoats and sprayed her tower of fake-blonde hair into a fixed, un-moveable bun that rested on the tippy-top of her head. She did our family’s food shopping at the Fort Monmouth Commissary, since her late husband had been a member of the armed services, and this alone made shopping suddenly fun for Alex and me because you had to cross through security to get in.

Bright eyed and tough as nails, Pauline pedaled around Little Silver on my dad’s bicycle in her housecoats, for daily exercise. When Alex and I arrived home from school, Pauline routinely asked ‘whadda-ya-wanta-forra-suppa?” I must have said something cheeky to her one day, because she looked straight at me over the kitchen counter and held my gaze for a minute before saying, “Oh. You think you’re smarter than me because I have an accent. You think I’m stupid.” I’m embarrassed to admit that Pauline was right, though I hadn’t realized it until that moment, and I treated her with full-on respect after that. As a matter of fact, it was precisely then that we became friends. The day my brother, while following me on his bike across the street was hit by a motorcyclist, she called my father right away at work before slamming down the receiver and whisking me off to the hospital, her Lincoln Continental only a few cars behind the ambulance. The nurse asked me multitudes of questions and there was only one I couldn’t answer; “Were his pupils dilated at the time of the accident?” I looked at Pauline, who fixed her blue eyes on the nurse, put her arm around me and said, ‘She’s not gonna know that.”

Pauline ran a kooky household and became like a mother figure to my father, who, believe me, desperately needed one. And in keeping with all her predecessors (except for Aunt Jill), Pauline was an amazing cook and excelled in the chicken category. My dad was in heaven. Her four year old granddaughter used to come over to spend the day with her, and with all of us once we were home from school, and things seemed overall to be running smoothly and consistently when Pauline got her pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

At the time, I didn’t recognize that diagnosis for the death sentence it was, and I listened doubtfully to my father’s explanation for why Pauline wanted to leave right away to live with her daughter. Silent and expressionless, he looked as he always did except for the tears that trickled a path down his otherwise stoic face. I had seen this before — once when our family dog died, the day the divorce was final and he showed up at my soccer practice, standing quietly next to the goal I was tending, and once more when we pulled out of the driveway after our last visit to Pauline. By that point, she resembled a forward facing skeleton, as if in a trance, breaking out every now and then to flicker her gaze over us.

Though it seems a sacrilege to follow Pauline up with anyone, well, such was our life. I introduce to you, Marge, the final character in our lineage of sitters.

This time my mother’s mother, Grandma Amy, conducted the interviews and hired Jersey-born Marge, who weighed at least two hundred and fifty pounds and smoked like a chimney. Marge wore a significant amount of caked-on make up, had dyed red hair and drove a pea-green bomb of an automobile. Despite Alex’s and my pleas to walk to school as we had for years, Marge insisted on driving us. “I wanchaz in the cah.” Why, we didn’t know, but we were prisoners who resorted to shrinking our bodies down as far as we could in the backseat of the guzzler, and scrambling out as quickly as possible at every drop-off. When we begged to walk home from school, Marge hit us with the same line and waited in the parking lot in the green bomb, a plume of cigarette smoke billowing from its barely cracked windows.

One summer day, bored, we consulted Marge on an idea for something to do. “Why donchas put some buttah on yah bodies and lie in the sunshine?”

“What?” We asked partially out of disbelief, and partially to savor the shocking absurdity again. That evening, she made a chicken soup that sent Alex choking before he pulled the small bone from his throat, and I suppose the most profound takeaway of this story is that it’s amazing that we both still eat chicken.

That night, Alex and I called a summit with our mother. Sitting on my bed, we rolled out our list of grievances and unprecedentedly, asked her to please, PLEASE…. fire Marge.

“Well, I think we need to give her a chance,” Connie replied in a thin voice — a voice that sounded foreign coming from her, and a voice that made me think we could finally, legitimately get away with it.

“How about no more babysitters? I’m twelve — we can take care of ourselves.”

Connie, I think surprised by our request and also seeing dollar signs, looked at me. That weekend, she took Marge aside, told her it wasn’t working out, and we were free.

Later that year, Grandma Amy died and Grandpa Oscar bought out my dad’s half of the house and moved in with us. Our gamut-ranging chicken dinners now were reduced to Swanson Chicken TV Dinners and Alex, Oscar and I were totally cool with that. And Oscar, as you will come to know, was delightful character who not only didn’t impede our freedom, he expanded it.

Little Silver #5 – Son of a Preacher Man? Actually, the Opposite

Dan McCallum was a year older than me, though I never knew him well. Or at all really, save for our friendly hellos in school. All I knew was that he was a nice kid, and his mom was a pastor at one of the churches in our town, Embury Methodist Church, situated appropriately on Church Street in Little Silver.

Dan McCallum was a year older than me, though I never knew him well. Or at all really, save for our friendly hellos in school. All I knew was that he was a nice kid, and his mom was a pastor at one of the churches in our town, Embury Methodist Church, situated appropriately on Church Street in Little Silver.

I was intrigued that Dan’s centered and cool mom was a pastor, because Connie was and still is an athiest zealot, though less vocal now in her older age. When I say zealot, I mean that she was religious in her beliefs and my brother Alex and I were home-schooled in Connie’s Church of Atheism. She readily threw about aphorisms such as “There is no GOD”, or “You should definitely read the Bible for an education – plus they’re good stories.” (We didn’t.) Or, “Jesus was a loving person in barbaric times. He taught people how to care for one another, but wasn’t the son of God because [as you may remember] there is no God.” When Connie worked at Planned Parenthood, a demonstrator once fixed a hand upon her car door as she was trying to drive out of the parking lot, exclaiming “God doesn’t want you killing little children!!” My mom shot back plainly and calmly with “Yes, God DOES” before nearly shutting the woman’s hand in the automatic window. Her view was that religion caused people to kill each other, though she did say that the Catholic Church had historically helped the poor in some incarnations. She didn’t think all religious people were lunatics of course, just that when something crazy went down, it was usually in the name of religion.

Connie had grown up going to a Quaker girls’ school in Providence and took us occasionally to the Quaker Meeting in nearby Shrewsbury, where she attended meeting and followed with her weekly “Witness for Peace.” This involved standing on the corner of Shrewsbury and Sycamore Avenues with other demonstrators holding signs, while drivers-by would honk and give you the thumbs-up or the bird, depending on their world views. When either happened, it was thrilling. Signs were obviously geared toward peace, and ours said something about education, which of course, I found dull. Always wanting a bit more drama, I was hoping for a more hard-hitting message, not something everyone could so easily get behind, but whatever – it was my mom’s sign, not mine. And as for the meetings themselves, in theory I really liked them and in reality I found them boring. A lot of waiting for people to speak, and when finally someone got up the guts, it was met with the opposite of applause – silence. That was a let-down.

Frankly, I found all meetings in houses of worship boring. When I slept over at my best friend Malinda’s house some Saturdays, I would attend 9 o’clock mass with her family the next morning at one of Little Silver’s other churches – The Church of the Nativity – and every time, I was ready for THE SHOW. After all, there were incredible stained glass depictions of pretty grizzly looking scenes. That was promising. But the sermons felt long and unconvincing. I suppose by then I was already ruined, or saved. Your call.

Anyway, back to the Methodist Church.

My classmate John Flynn, who also identified as a singer by age 8, went to the Methodist Church Choir and one day in school he told me about the outfit he got to wear. Green flowing pants and a white, blousy shirt. As he described it to me, my eyes widened. “Wait, could you wear it to school?” At that point, his tone became slightly more subdued. “Well, I don’t think you’d want to do THAT…”

Hmm. I struggled to picture a white flowing blouse I wouldn’t wear to school but trusted that he knew what he was talking about. To give you a sense, John has his own cabaret show in LA now, and he had a wider capacity for ideas than most other Little Silver residents. As for me, I loved singing and wearing costumes, so I set my mind on this choir and told my mother I wanted to go to church to sing in it. As is her way, she didn’t skip a beat. “Okay, we’ll have to get you some clothes then,” and she proceeded to take me to Marshall’s where we scored a wrap around kilt (had that big safety pin that I’d so coveted on others – pardon the sin) and a white cotton turtleneck.

Well, I felt so fucking sophisticated, nobody could stop me now.

That Sunday, I walked to the church and announced to Pastor McCallum that that I wanted to join the choir. A lovely person who easily obliged, she showed me to the basement where I went through one run-through before I was handed my outfit. Finally, it was in my hands, and it was full-on Gospel-Choir-Awesome. John was right, though; I couldn’t see a way in which I would get away with wearing it at school. As an aside, I could be, in those days, sometimes flamboyant. It wasn’t until 7th grade when I came into school wearing a heavy black cape and was told by a popular girl that she was going to kick my ass after school, that I cowed. Right away, actually. Never having never having traveled in ass-kicking circles, I didn’t for a moment consider myself tough enough to rise to the occasion. Rather, I spent the afternoon looking over my shoulder and quivering in fear over my impending pummeling, which strangely never happened. The grace of God, you might ask? I considered it. I took it as a pardon and went straight to the Gap that afternoon, never to show my colors again.

Yep, that’s the kind of girl I am.

For weeks I walked the half mile to church on Sundays to sing and sway. Of course, we were all white so the swaying was disappointingly minimal, but the feeling of hearing, or almost not-hearing, my own voice blend with the bigger, more resonant group voice was a real high. A religious experience, you might say, and to this day, “Go Tell it on the Mountain” remains one of my favorite songs.

(Remember Dan McCallum? Are you wondering how I might meaningfully weave him into the fabric of this tale now that we’re drawing to a close? Well, I just plain didn’t want to edit him out. After all, he was a nice guy, so why be a jerk? Plus it’s the privilege my indie-press here affords me.)

Church singing was great until I quit for some unremarkable reason – maybe John left so I did? With this, I had to turn in the outfit but by then I had soaked in all the magic that its polyester fibers had to offer. I learned later that many singers honed their passion for music by singing in church: Tina Turner, Elvis Presley, Marvin Gaye – Steve Curtis for gosh-sakes! And though I couldn’t subscribe to the organized religion part, church was a stellar first venue for me. To me, this is the strongest endorsement of church outreach yet – that it provided a passionate musical outlet for the Daughter of an Athiest.

————-

Addendum: I contacted John on Facebook to let him know of this essay, can I use his name, etc. and sent it his way for review. Lovely as ever, he dug the essay and told me somewhat apologetically that he never sang in the Methodist Choir, but he wouldn’t call me out! Speaking to the manipulation of memory, this person I spoke with so many years ago who encouraged me to join the chorus is SO CLEARLY John. I can even see his rosy face during the conversation. And if it wasn’t him, I just don’t know who it could be. So one of us is confused and it’s likely me. At the same time, I ain’t lying, folks! Of course, I’m still waiting for John to write me with an ‘Oh yeahhhhh….. now I remember.”

Take it with salt, folks.

Little Silver #4 – Atkin

My father did a handful of things that no one else I know has done.

My father did a handful of things that no one else I know has done.

1.) He swallowed a diamond, wrapped in chewing gum and saran wrap, to get it out of the Belgian Congo. Age 16.

2.) He swam out to an anchored cruise ship, touched it with his hand, smiled and waved to the passengers before swimming back to shore. Age 14.

3.) Using a machete, he chopped the head and the tail off of a Banana Snake. Age 15.

These were my favorite stories that, as a kid, I asked him to tell and re-tell in hopes that there was one more detail. How Little Silver, NJ, that Irish-and-Italian Catholic town, landed an Egyptian-born Armenian immigrant was luck of the draw, I guess.

In 1977, Atkin and Connie Simonian moved their family to Little Silver, NJ from Wheaton, IL because, in my New England-born mother’s retelling, “I told him I was going to leave him unless we moved back east.” In 1979 their divorce was made final, so I guess the midwest wasn’t the only problem.

Something about family life, or a marriage to my mother, or professional demands, or his strict, middle-eastern upbringing, or some combination of the above, shut my father down pretty whole-heartedly. Alcohol helped. One day in Wheaton, while mowing the front lawn, Atkin fell over and passed out right there in the grass. He’d had 6 beers. Our across-the-street neighbor, Arlene, came storming over, sat him up and gave him hell, lecturing straight into his glazed eyes about what a disgrace he was to God and his family, as my mom looked on, smiling.

When the custody agreement came down, I was 8 years old. Our mom told us we would live with her six months of the year and with him six months of the year. My brother, Alex, and I would stay full-time in the house while they moved in and out. We were stunned. The thought of living with our father WITHOUT our mother was akin to hearing you were getting set to live with the man who checks the electricity meter. That’s how well we felt we knew our dad.

Ok.

The rotation of move in/move out went on for 6 years. As Atkin was fired from job 1, then 2, then 3 for drinking, his daily drinking routine became more of that – a routine. He drank in his office at the back of the house, and by the evening he was ready to pick a fight about something. Obviously we couldn’t be honest with him about how unhappy we were, so half of each year felt like a form of imprisonment. Our mother called daily, but the more his alcoholism progressed, the more paranoid Atkin became; he listened in on our phone conversations while she repeatedly demanded he hang up. She threatened court, etc., but nothing really helped, which is partially my fault.

But more on that a bit later.

Our father’s alcoholism was a despairing situation. There are countless stories that would make this chapter insufferably long, but some memories stick out. One of his best friends from Egypt, who now lived in north Jersey, used to bring his family to Little Silver to visit us and go to the beach. I loved this family of three boys because they were fun to hang out with and a break from our otherwise mostly solitary family life. There were always shenanigans afoot – wrestling, hiding, silly games, and though their father was strict with all the boys, he treated me like an innocent princess. Their mom was an easy-going, fun-loving lady who, pre-divorce, had loved to yuk it up with my mom over various absurdities.

One day, Atkin got so drunk he could barely walk and when they were pulling out of our driveway to leave, my dad, laughing and stumbling, slurred, “I wanna kiss your wife!” Mortified, I watched the movie of him holding onto the car door…. they went from trying to laugh it off to asking him, increasingly nervously, to please let go before they finally drove off, dragging him only a little bit before his hands came dislodged from her window and he fell to his knees in the driveway. He was still laughing, and to their credit, they were still his close friends.

Little Silver had about four main roads in its one square mile, and we’d swerved our way home through them on countless occasions. With no traffic lights, we were entrusted to stop signs, which, if you’re drunk at night, are easy to miss. The fact that we often-enough narrowly avoided crashing into trees had the odd effect of making me feel completely safe in a car with him, sort of the way you trust that a rollercoaster won’t roll off its track (though of course your odds are quite a bit better on a rollercoaster than in a car with a drunk driver).

Perhaps the most telling symptom of my father’s illness was that he’d stay up at night and ask me to talk with him. Alex, the extremely book-wormy and gentle animal-lover sort, would steer clear, staying in his room. He didn’t want to be a target, and often was if he was out in the open for not being the sports enthusiast, son-archetype that my father wanted. Protective of my brother, pitying of my father, I felt invincible, too young to feel vulnerable to or recognize that brand of danger. As a matter of fact, in those days I leaned into danger with an interest in knowing more of the world.

On occasion, Atkin would stare straight ahead and say through watery eyes. ‘Will you take care of me when I’m sick and dying in 10 years?”

“Yes,” I lied. Or so I thought.

I steered him toward his bedroom at the end of the hall for many nights until I figured out that the hallway was narrow enough that he could bump his way down, pinball-style, and make it through the bedroom door on his own.

One mom-weekend about 2 years in, we stayed with her at her newly-rented, run-down but oddly beautiful apartment one town over, in Red Bank. It was nearly empty, save for three beds, a chair, and an old wasp’s nest in a corner of the kitchen ceiling that had lived there longer than anyone else had. We asked her if she could please try again to get full custody of us. She said what she usually said, and was true – she didn’t have the money – but she listened intently as she always did, and based on the stories we were telling her, decided to go for it one last time.

We silently awaited the day with anticipation, and when it came, Alex and I were requested to show in court as well. I pictured a courtroom, a jury, a la To Kill A Mockingbird, which I’d recently seen on TV — high drama with a handsome, charismatic lawyer. However, in the hallway outside of the courtroom, there stood only the four of us: my mom, my brother, and me — and my father, five or so yards away from us, looking cleaned-up in a three piece suit and, I saw, very sad.

My parents’ respective (unhandsome and uncharismatic) lawyers joined us as we walked into an empty courtroom. When Judge Kennedy emerged from the back, he motioned for Alex and me to join him in his chambers. At ages 10 and 9, we dutifully followed and found our seats across from him. Kennedy looked directly at me.

“Nobody will know what we talked about in here, I assure you. Erika, we’ll start with you; who do you like living with better, your mother, or your father?”

I was horrified. How would my father not know what we said if Kennedy took only us into his chambers and came out with a verdict? Having been under the impression that others would be called on to relate our stories, my immediate sinking realization was that my father would die, and I mean literally – if he knew we, his children, had rejected him.

I paused. “We like living with them both the same.”

“Both the same. Ok, Alex?”

Alex barely looked at me or the judge. “Both the same too”, he said quietly. It was understood in those days that Alex did, said, and agreed with anything I said, due to his extreme shyness and general discomfort in the world.

“Ok, then, come with me.” He stood up, escorted us back to the courtroom where he pronounced that there would be no change to the custody agreement.

I don’t remember what happened after that; my mind goes white when I try to recall the details. What I do remember is that my father smiled, then we said goodbye to him and drove back to the house in Little Silver with my mother. Through her bedroom door, I heard her sobbing into the night. She didn’t talk to me for a few days, except to tell me how I’d ruined the whole thing. I begged her through my own tears to see if she could call them — there had to be a way to reverse it. There wasn’t.

About Atkin, he was sincerely interested in people, sociable, educated, and fluent in Armenian, French, English and Arabic; he was a great tennis player, a fabulous cook and a chemist who had invented and patented several metal plating alloys. He was also worldly, handsome and funny — when he wasn’t a mess. His friends in Little Silver all said the same thing; “He’s so wonderful when he’s sober!” A handful of neighborhood moms had crushes on him, which made my brother and me sick, but still. He attended most all of my plays and soccer games (which was somewhat stressful for me, being a good enough player but not ever the best player, etc., and he was mighty competitive). He took me out to lunch, he was the one to take me to visit colleges I was interested in, he was involved in all the ways a good-dad-on-paper is. But he was emotionally twisted into a knot on the inside. He was sent suddenly and alone to America at age 16 as his family fled the Belgian Congo in all directions to escape a governmental coup, and he settled with an aunt and cousins he’d never met. They were a loving bunch and became his family, but he rarely saw his birth family ever again.

All this to say that Atkin was lost from the start. And though he didn’t say as much, he was heartbroken too.

Many things transpired. My mother’s father, Oscar, bought out my father’s half of the house after 6 or 7 years of this. By then Atkin was not able to hold down a job and he needed money. Oscar’s purchase afforded Atkin a dignified exit from a sinking ship. He left Little Silver, bought a small condominium nearby and fell ill not long afterward. He died 9 years later in his own bed with Alex and me by his side.

As promised, I’d taken care of him on and off for his last two years during his bout of cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, found primarily in heavy drinkers and smokers.

When he died, I was 22. I was ready to leave Little Silver and start my life.

Little Silver #3 – Aunt Jill

One version of my childhood is that I was half-raised by a British WWII nurse. Aunt Jill lived with us for only 3 years before she retired at age 72, and she is one of the only consistent players in the enterprise of bringing up the two children at 301 Rumson Road in Little Silver, NJ.

Once a single mother, Connie got a job in NYC. Yes, she longed to get back to her pre-children working life, but the city was where she could earn enough to cover the bills. Knowing she’d be gone most of each weekday due to the long commute, she placed an ad in The Asbury Park Press for a live-in caretaker. In walked Jill Tompkins with one suitcase in hand.

Jill became a fixture in the dry, mile-square town of Irish and Italian catholic families who had lived in Little Silver for generations. First of all, nobody had live-in babysitters. Secondly, her British accent made it such that anything she said sounded authoritative and slightly haughty, so people tended not to argue with her. And third, she got to work right away. With a skill level on par with Henry Higgins, she transformed my 7 year old brother Alex and 8 year old me from savages into people who could eat with a knife and fork. She taught me to make my bed with hospital corners, a skill I was pretty proud of and sure nobody else I knew possessed (nor did they likely care about, but I did). She got things running smoothly in our lives, and we were not the only ones to notice. Kids who weren’t allowed to come to our house to play when the news hit that my parents were divorcing were suddenly allowed once Jill was on the scene. For those few years, she provided a real stability as our two parents took turns moving in and out of the house every six months.

Even though Aunt Jill was as serious a hard-ass as we had yet known, she seemed to sincerely enjoy our company. She rewarded any good behavior with Certs (British-esque, patrician-type mint) or Mentos, and on special occasions, took us to McDonald’s. She loyally drank tea out of the pharmacy-bought, flowered teacup I gave her one year for her birthday, and when it broke, she glued it back together and still used it despite its slow leak. She even crocheted Alex and me elaborately sectioned blankets for our beds; mine in two oddly matched colors that weren’t exactly pleasing to the eye – a saturated royal blue and potent mustard yellow. I LOVED this blanket and my mother kept it for me through the years and various re-locations, and it now stands as a pretty singular relic of my otherwise pretty relic-less childhood.

The best thing about Jill was that she had a story for just about any animal we brought up, and I suspected her, after some time of regaling us with tales of personal run-ins with the most obscure jungle animals we could find in our encyclopedia, to be a chronic liar. But like many kids, I preferred a good story to the truth any day, and hers were engaging, colorful and action-packed. She had worked in Africa as part of the North African Campaign during the war and, for example, while walking from the commissary to the hospital, she once spotted an ocelot or a puma in a tree above, ready to pounce. In none of her stories did the animals ever get shot or otherwise perish, and she narrowly escaped possible attack through several clever displays of agility. Though once in a while, a (probably handsome) hospital doctor came to her rescue.

(I should add that in support of the liar theory, Aunt Jill’s real name, as we found out through letters that came to her at our address, was Lorna Tompkins. We soon discovered that we got in big trouble if we even jokingly referred to her as Lorna. So we didn’t.)

Jill was a widow, and we had come to know Eddie, her husband, as nothing more than a personality-less ghost, mostly through her notable LACK of stories about him, even when probed for info. On the weekends when my mother or father were home from work, Aunt Jill would drive 30 miles south to stay with her friend, Mrs. Rowlands, an elderly American widow. Occasionally she took us to Mrs. Rowlands’ cluttered but pleasant apartment for a weeknight dinner, where we learned that they shared the bedroom and seemed to have a gentle and knowing companionship.

If Aunt Jill was guilty of any crime, it was of being old-fashioned in the wrong way for my forward-thinking and extremely liberal mother, who had volunteered at Planned Parenthood in the early 70s and worked there again after she had retired from her NYC job later in life. One day Jill’s achilles heel got the better of her when I was splayed out on the couch reading a book and she practically spat, ”Sit like a lady!” It wasn’t the first time we’d had this “conversation”, and for whatever reason on this day I retorted (with attitude, I’m sure), “But I don’t WANT to be a lady!” and she smacked me. I don’t think it was on my face; I don’t really remember, and it didn’t hurt, but it did surprise me.

Connie did not have many rules, but there was definitely one: nobody was allowed to hit us. And that night after we’d gone to bed, when relating the tale of the day to my mom, Jill continued with, “And I think you should have Erika see a psychologist because she’s patterning herself after you.” Years later Connie told me this story, and how insulted she’d been. But after reading Jill some more refined version of the Riot Act, she didn’t fire her, because to start with, my mom is not a hot head, and also I think because she recognized that she needed Jill. We were in so many ways well-cared for. Jill could hang with my parents’ unorthodox custody arrangement, and previous babysitters couldn’t or didn’t because they were elderly immigrant ladies who led old-world lives; they didn’t want to live in the house during my dad’s tenure, not because he was threatening, but because he was a man who wasn’t their husband and their husbands didn’t want them living in another man’s house. Whatever the case, Jill was old, tough, indebted to no one, and she didn’t bat an eyelash at any of it.

After she retired, Jill left a vacancy. My mom was still working and we had a panoply of sitters that followed her, but there was never another who loved us, with whom we felt as comfortable, and whom we loved back. And strangely or not, I don’t remember what followed, but I think we saw Aunt Jill only a handful of times after her retirement. Jill had been in touch to ask if we would back-pay into the social security system on her behalf, which my mother did. After Mrs. Rowlands died, her family wrote Jill out of everything and she moved into an assisted living home on the Jersey shore. One Saturday about 10 years after her tenure in our house, Connie and I drove out to see her. Obviously older, she was tiny and vulnerable in a way I’d not known her to be, telling us in a small voice that she was living on a shoestring budget and could we help her out? She’d recently asked my father for money and he’d obliged, but that day my mother said no, that she didn’t have it. We stayed a bit longer and on our drive home I looked out the window while my mother assured me that Aunt Jill was being well taken care of.

That was the last time I saw her.

Recently, Connie told me a story. Two years after that visit, she’d received a message from Jill on the machine, asking for a call back. It was my mom’s last night in New Jersey, as she and her new husband had sold their house and were leaving for the retirement life in South Carolina. Connie deleted the message, and the phone was disconnected for good the very next day.

Three days later, my father died of cancer. And while everything bleeds into everything else, that is a story for another day.

Little Silver #2 – The House

As quiet and beautiful as it was, Little Silver invited me into its folds with an introductory tale of tragedy. It was like starting a friendship with a punch in the gut; if you get through it, you’re best friends for life.

As quiet and beautiful as it was, Little Silver invited me into its folds with an introductory tale of tragedy. It was like starting a friendship with a punch in the gut; if you get through it, you’re best friends for life.

I was 5 when I first stepped into our empty house with my brother and parents and the realtor. Holding my mom’s hand and looking down at the orange shag wall-to-wall carpet in the family room, I asked her in a whisper who had lived here before us.

She told me about the family of three. One night earlier that summer, the son, 17 years old, had been doing 360s in his car on a joyride on one of the high school ball fields up the road. The gas cap popped off with a thunk, and to investigate the situation, he knelt down to check around the car, lighting a match to get a closer look. The explosion followed, and he and his girlfriend were helicoptered to the Brooklyn Burn Center where they both died the next morning.

“But where did his parents go?” She told me that they moved down the road. A deliberate move, just to get out of this house.

We resumed our walk-through behind the realtor as my small brain ran that scene over and over. I tried to picture his parents. My thoughts returned to them often throughout the years as a totem of tragedy. What was their life like now? Did they talk to each other or did they live in silence? I wondered which house down the street contained their sorrow. A couple of years later when I sold girl scout cookies door-to-door, there were two houses that never answered in all the years I knocked. The brush got thicker and wilder as I neared those houses by the woodsy bird sanctuary and I crossed through lots of thicket to get to those doors with seemingly no-one behind them. But a car in the driveway, always.

Maybe they don’t answer the door to little kids. Maybe they can’t, I thought.

Our house that had been marked by tragedy continued on its protracted-tragic schedule, though never again as dramatically as in the manner to which I’d been introduced to it. My brother and I loved our ranch-style home, same as all the others on our street, and had lots of happy times there. But all lives have sorrow and secrets, and many of ours incubated in that house. My mother immediately named it ‘The Turning Point’; months before she would separate from my father, she announced a little too excitedly, “So much changes here!” It fell into some disrepair soon after we moved in, since we lived there for only a year before Connie left Atkin, and due to the lawyer fees and costs of separation and divorce, maintaining the house and renting an apartment, neither of them had the funds to fix much.

We loved it so much, we didn’t even notice. We were kids, we had circuitous hallways, we had a wild, overgrown yard to run around in, and we had the stories in our heads.

Erika’s Little Silver Memoir #1

As we get toward this album’s release into the wild, I’ve been reflecting on our inspiration for the band’s name, the mile-square town of Little Silver, NJ, where I grew up in the 70s and 80s. Like everywhere else, it has changed. Little Silver is now crowded with New Yorkers who found a Jersey Shore haven for their families. The town has since widened its main streets and gained some traffic lights to keep up with its increased fancy car-count, but back in the day it was a sleepy, mostly working-class town that housed one gas station, one luncheonette, and was only 4 miles from the Atlantic Ocean.

My parents picked the town in 1977, based on its proximity to the beach and because, as my mother told it, she loved the name. The story goes that in 1667, white settlers bought the town from the Native Americans for ‘a little bit of silver’. So pleased with their deal, the settlers decided to name the town after this victorious exploitation.

Still, we loved the name.

In the next weeks, I’ll be posting anecdotes about the characters in and around my family who lived there. Stay tuned if you want a break from the news and any other, perhaps more worthy passages of time.