Little Silver #4 – Atkin

My father did a handful of things that no one else I know has done.

My father did a handful of things that no one else I know has done.

1.) He swallowed a diamond, wrapped in chewing gum and saran wrap, to get it out of the Belgian Congo. Age 16.

2.) He swam out to an anchored cruise ship, touched it with his hand, smiled and waved to the passengers before swimming back to shore. Age 14.

3.) Using a machete, he chopped the head and the tail off of a Banana Snake. Age 15.

These were my favorite stories that, as a kid, I asked him to tell and re-tell in hopes that there was one more detail. How Little Silver, NJ, that Irish-and-Italian Catholic town, landed an Egyptian-born Armenian immigrant was luck of the draw, I guess.

In 1977, Atkin and Connie Simonian moved their family to Little Silver, NJ from Wheaton, IL because, in my New England-born mother’s retelling, “I told him I was going to leave him unless we moved back east.” In 1979 their divorce was made final, so I guess the midwest wasn’t the only problem.

Something about family life, or a marriage to my mother, or professional demands, or his strict, middle-eastern upbringing, or some combination of the above, shut my father down pretty whole-heartedly. Alcohol helped. One day in Wheaton, while mowing the front lawn, Atkin fell over and passed out right there in the grass. He’d had 6 beers. Our across-the-street neighbor, Arlene, came storming over, sat him up and gave him hell, lecturing straight into his glazed eyes about what a disgrace he was to God and his family, as my mom looked on, smiling.

When the custody agreement came down, I was 8 years old. Our mom told us we would live with her six months of the year and with him six months of the year. My brother, Alex, and I would stay full-time in the house while they moved in and out. We were stunned. The thought of living with our father WITHOUT our mother was akin to hearing you were getting set to live with the man who checks the electricity meter. That’s how well we felt we knew our dad.

Ok.

The rotation of move in/move out went on for 6 years. As Atkin was fired from job 1, then 2, then 3 for drinking, his daily drinking routine became more of that – a routine. He drank in his office at the back of the house, and by the evening he was ready to pick a fight about something. Obviously we couldn’t be honest with him about how unhappy we were, so half of each year felt like a form of imprisonment. Our mother called daily, but the more his alcoholism progressed, the more paranoid Atkin became; he listened in on our phone conversations while she repeatedly demanded he hang up. She threatened court, etc., but nothing really helped, which is partially my fault.

But more on that a bit later.

Our father’s alcoholism was a despairing situation. There are countless stories that would make this chapter insufferably long, but some memories stick out. One of his best friends from Egypt, who now lived in north Jersey, used to bring his family to Little Silver to visit us and go to the beach. I loved this family of three boys because they were fun to hang out with and a break from our otherwise mostly solitary family life. There were always shenanigans afoot – wrestling, hiding, silly games, and though their father was strict with all the boys, he treated me like an innocent princess. Their mom was an easy-going, fun-loving lady who, pre-divorce, had loved to yuk it up with my mom over various absurdities.

One day, Atkin got so drunk he could barely walk and when they were pulling out of our driveway to leave, my dad, laughing and stumbling, slurred, “I wanna kiss your wife!” Mortified, I watched the movie of him holding onto the car door…. they went from trying to laugh it off to asking him, increasingly nervously, to please let go before they finally drove off, dragging him only a little bit before his hands came dislodged from her window and he fell to his knees in the driveway. He was still laughing, and to their credit, they were still his close friends.

Little Silver had about four main roads in its one square mile, and we’d swerved our way home through them on countless occasions. With no traffic lights, we were entrusted to stop signs, which, if you’re drunk at night, are easy to miss. The fact that we often-enough narrowly avoided crashing into trees had the odd effect of making me feel completely safe in a car with him, sort of the way you trust that a rollercoaster won’t roll off its track (though of course your odds are quite a bit better on a rollercoaster than in a car with a drunk driver).

Perhaps the most telling symptom of my father’s illness was that he’d stay up at night and ask me to talk with him. Alex, the extremely book-wormy and gentle animal-lover sort, would steer clear, staying in his room. He didn’t want to be a target, and often was if he was out in the open for not being the sports enthusiast, son-archetype that my father wanted. Protective of my brother, pitying of my father, I felt invincible, too young to feel vulnerable to or recognize that brand of danger. As a matter of fact, in those days I leaned into danger with an interest in knowing more of the world.

On occasion, Atkin would stare straight ahead and say through watery eyes. ‘Will you take care of me when I’m sick and dying in 10 years?”

“Yes,” I lied. Or so I thought.

I steered him toward his bedroom at the end of the hall for many nights until I figured out that the hallway was narrow enough that he could bump his way down, pinball-style, and make it through the bedroom door on his own.

One mom-weekend about 2 years in, we stayed with her at her newly-rented, run-down but oddly beautiful apartment one town over, in Red Bank. It was nearly empty, save for three beds, a chair, and an old wasp’s nest in a corner of the kitchen ceiling that had lived there longer than anyone else had. We asked her if she could please try again to get full custody of us. She said what she usually said, and was true – she didn’t have the money – but she listened intently as she always did, and based on the stories we were telling her, decided to go for it one last time.

We silently awaited the day with anticipation, and when it came, Alex and I were requested to show in court as well. I pictured a courtroom, a jury, a la To Kill A Mockingbird, which I’d recently seen on TV — high drama with a handsome, charismatic lawyer. However, in the hallway outside of the courtroom, there stood only the four of us: my mom, my brother, and me — and my father, five or so yards away from us, looking cleaned-up in a three piece suit and, I saw, very sad.

My parents’ respective (unhandsome and uncharismatic) lawyers joined us as we walked into an empty courtroom. When Judge Kennedy emerged from the back, he motioned for Alex and me to join him in his chambers. At ages 10 and 9, we dutifully followed and found our seats across from him. Kennedy looked directly at me.

“Nobody will know what we talked about in here, I assure you. Erika, we’ll start with you; who do you like living with better, your mother, or your father?”

I was horrified. How would my father not know what we said if Kennedy took only us into his chambers and came out with a verdict? Having been under the impression that others would be called on to relate our stories, my immediate sinking realization was that my father would die, and I mean literally – if he knew we, his children, had rejected him.

I paused. “We like living with them both the same.”

“Both the same. Ok, Alex?”

Alex barely looked at me or the judge. “Both the same too”, he said quietly. It was understood in those days that Alex did, said, and agreed with anything I said, due to his extreme shyness and general discomfort in the world.

“Ok, then, come with me.” He stood up, escorted us back to the courtroom where he pronounced that there would be no change to the custody agreement.

I don’t remember what happened after that; my mind goes white when I try to recall the details. What I do remember is that my father smiled, then we said goodbye to him and drove back to the house in Little Silver with my mother. Through her bedroom door, I heard her sobbing into the night. She didn’t talk to me for a few days, except to tell me how I’d ruined the whole thing. I begged her through my own tears to see if she could call them — there had to be a way to reverse it. There wasn’t.

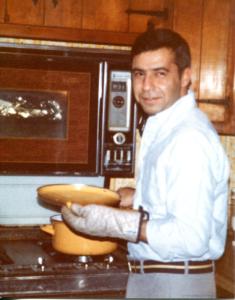

About Atkin, he was sincerely interested in people, sociable, educated, and fluent in Armenian, French, English and Arabic; he was a great tennis player, a fabulous cook and a chemist who had invented and patented several metal plating alloys. He was also worldly, handsome and funny — when he wasn’t a mess. His friends in Little Silver all said the same thing; “He’s so wonderful when he’s sober!” A handful of neighborhood moms had crushes on him, which made my brother and me sick, but still. He attended most all of my plays and soccer games (which was somewhat stressful for me, being a good enough player but not ever the best player, etc., and he was mighty competitive). He took me out to lunch, he was the one to take me to visit colleges I was interested in, he was involved in all the ways a good-dad-on-paper is. But he was emotionally twisted into a knot on the inside. He was sent suddenly and alone to America at age 16 as his family fled the Belgian Congo in all directions to escape a governmental coup, and he settled with an aunt and cousins he’d never met. They were a loving bunch and became his family, but he rarely saw his birth family ever again.

All this to say that Atkin was lost from the start. And though he didn’t say as much, he was heartbroken too.

Many things transpired. My mother’s father, Oscar, bought out my father’s half of the house after 6 or 7 years of this. By then Atkin was not able to hold down a job and he needed money. Oscar’s purchase afforded Atkin a dignified exit from a sinking ship. He left Little Silver, bought a small condominium nearby and fell ill not long afterward. He died 9 years later in his own bed with Alex and me by his side.

As promised, I’d taken care of him on and off for his last two years during his bout of cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, found primarily in heavy drinkers and smokers.

When he died, I was 22. I was ready to leave Little Silver and start my life.